Mentoring “Bill of Rights” for Students in Research Labs: The relationship between a student and their research advisor is a mentor-mentee relationship. These relationships are one of the most important you will develop as a student and later in your professional career. As with all relationships, you should be aware of the complexities and be able to recognize productive as well as unproductive aspects of your mentor-mentee relationship. Most importantly, you should ask questions of your mentor and identify others that can help you navigate this important and powerful relationship.

What is a mentor? Perhaps most importantly, a mentor is someone who takes sincere interest in the future growth and development of their mentee (i.e., you!). A mentor is someone who shares knowledge and serves as an experienced and trusted advisor. Check in with yourself periodically about how you feel about your interactions with your mentor. Remember, as with all relationships, it can take time and effort to optimize your relationship with your mentor. There’s always room for improvement. Do not hesitate to reach out for advice or help.

Here are some of the roles your mentor might serve in your time in the lab. Remember, you may have more than one mentor in a research lab (e.g., your PI and a graduate student):

Teacher: Mentors help mentees develop as researchers by teaching specialized knowledge and technical skills. Mentors should always provide safety and technical training.

Advisor: Mentors can advise mentees on their research agenda and goals.

Supervisor: Mentors often, but not always, supervise a mentees work as employees (research assistant or postdoc for example).

Professional Development Coach: Mentors should advise and support career development. For undergraduates, this may mean helping them manage their course load as well as navigate applications for graduate/professional degree programs. Mentors should never create “if, then” (i.e., quid pro quo) for supporting students academic or professional growth.

A guide to the culture of research: Mentors can help socialize mentees into the community of scientific research. This includes making mentees aware of the ethical, political and social elements of interacting within the academic community or organization.

Advocate: Mentors should support their mentees when there are questions, concerns or difficulties. Mentors should be concerned about the general well-being of their mentors, including helping you find a healthy work-life balance. A mentor should never ask you to accommodate a schedule that is unhealthy for you or that compromises your ability to maintain your academic standing.

What should you look for in a research mentor?

Clarifying expectations: One of the first interactions you have with a mentor is for them to clearly define their expectations of you. How many hours do they expect you to be in lab, or working on the project? Are there specific deliverables (i.e., lab notes, presentations, reports)? How do you communicate about your research-course work balance?

Being an honest and fair person: Mentors should be available and committed, be knowledgeable about appropriate practices and professional ethics, engage in continuing education about research and mentoring strategies, and teach by both words and example of what those roles entail. At the same time, a mentor has to be honest with the mentee about the limits of their expertise.

Avoid conflict between roles: Mentors must look after both the mentees progress in research while also helping their mentee be successful in their academic studies. Mentors need to balance their personal and professional roles and goals with their mentoring roles and goals, and avoid abusing their power.

What should you bring to the mentor-mentee relationship?

Willingness to communicate: Mentors expect their mentees to maintain consistent communication and to be reliable, responsive, prepared and organized. Mentors expect mentees to communicate their ideas, concerns, needs, and expectations and to be willing to ask questions or ask for help. Mentors expect that their mentees will be able to give and receive feedback.

Positive attitude and work ethic: Mentors expect students to be enthusiastic about their project, and to be willing to put in the effort necessary. Mentors expect students to be self-motivated, disciplined and committed. Mentors hope that students take the initiative, challenge themselves, take risks (while being safe).

Signs that you might want to seek advice about your mentor-mentee relationship:

If you are feeing overly anxious about going into lab (e.g. you’re losing sleep over the thought of your lab project).

If your interactions with your mentor are creating highly charged emotional reactions (e.g., crying or raised voices).

If you encounter a “if-then” scenario where your mentor is withholding support in exchange for work or some task.

If you feel that you mentor or others in your research environment are not following the UC Davis principles of community.

Who can you go to if you have questions or concerns about your mentor-mentee relationship?

Peers: Talk to other students in the lab or in your major. Check in with their experiences and compare them to yours.

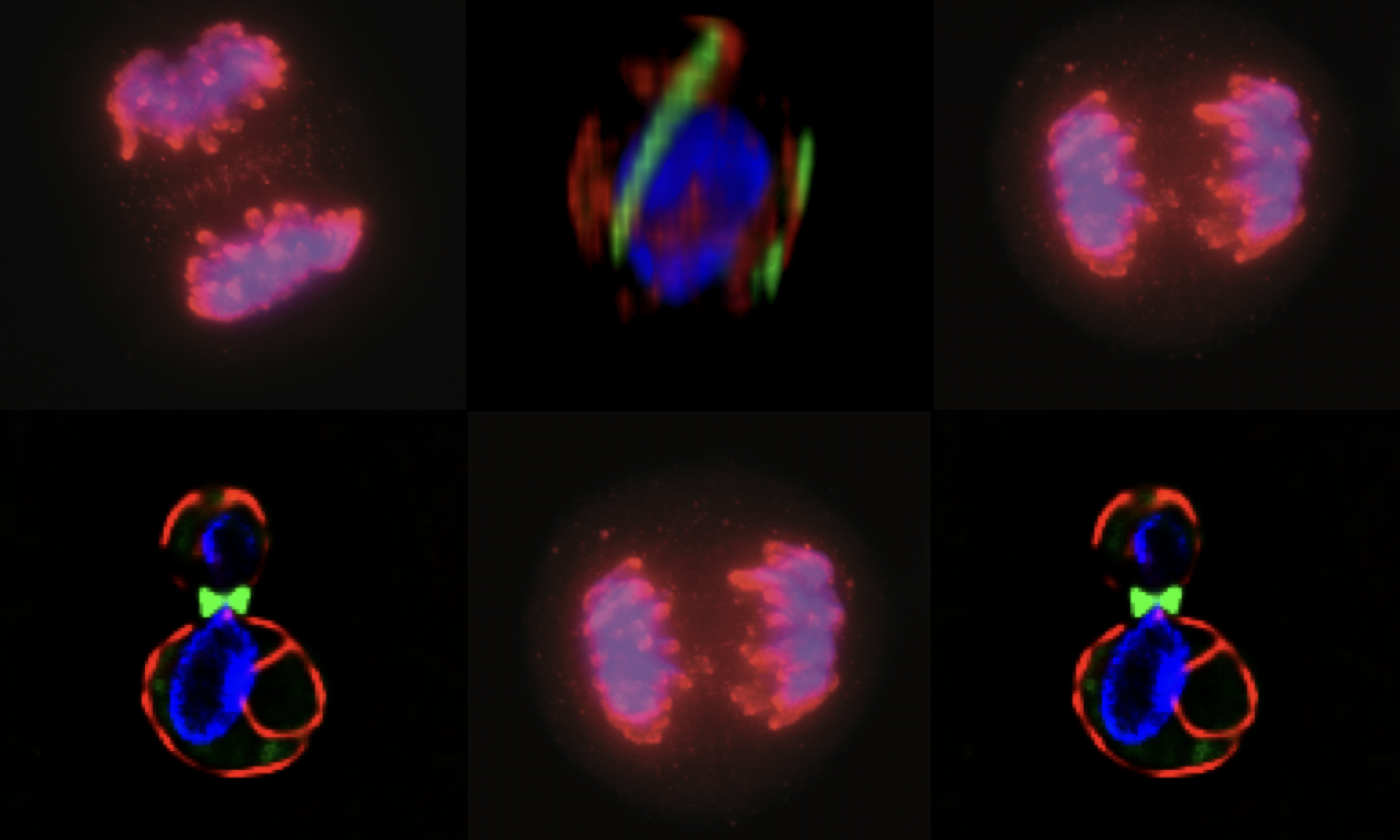

MCB Department: The department chair and vice chairs are committed to ensuring the best possible mentor-mentee relationships. Contact Dr. Jodi Nunnari (Chair of MCB) or Dr. Ken Kaplan (Vice Chair of Instruction) if you have concerns or questions about your mentor-mentee relationships. You can also talk to a trusted professor about these issues.

Academic Advising: Your BASC advisor can direct you to resources to help you address concerns or problems you might encounter.

UC Davis HDAP (Harassment and Discrimination Assistance Program) has a portal for reporting a variety of inappropriate behaviors.

Other resources:

UC Davis Grad Studies Mentoring Site

UC Davis BMCDB Mentoring Guidelines

Conflict management and mental health resources (BMCDB)